Addresses in Japan are fascinating. There’s a system to it, with lots of exceptions and special cases. And just recently there was an announcement about the city I am technically considering home-base when in Japan: Kawasaki (川崎).

As you see in the title of this post there’s a kanji character missing:

川崎 means “Kawasaki” – just the name itself, like used on signs and such.

川崎市 means “Kawasaki-shi” – the name got extended by -shi which in itself will signal that the name before is a city.

And then there is this other kanji in the title: 区. It is spoken as “ku” and basically means “ward”. It’s a bigger city broken down into separate wards.

Not all cities in Japan are required to differentiate into wards – just the ones considered big enough. Kawasaki was considered big enough by 1972 to name out it’s wards.

And so its the Nakahara-ward (中原区) I am usually staying to be more specific on the Kawasaki-home-base-statement at the beginning of this post.

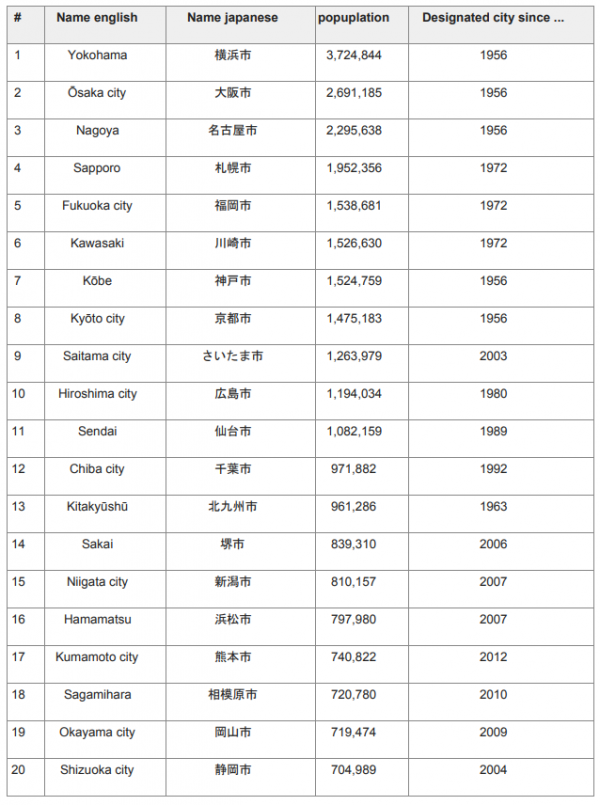

And the designated cities are somehow ranked according to their population. The news here is that apparently given the 2019 population numbers Kawasaki has improved it’s position among all big designated cities by one rank:

Some more details then to the japanese addressing system:

Japanese addresses begin with the largest division of the country, the prefecture. Most of these are called ken (県), but there are also three other special prefecture designations: to (都) for Tokyo, dō (道) for Hokkaidō and fu (府) for the two urban prefectures of Osaka and Kyoto.

Following the prefecture is the municipality. For a large municipality this is the city (shi, 市). Cities with a large enough population, called designated cities, can be further broken down into wards (ku, 区). (In the prefecture of Tokyo, the designation special ward or tokubetsu-ku, 特別区, is also used for municipalities within the former city of Tokyo.) For smaller municipalities, the address includes the district (gun, 郡) followed by the town (chō or machi, 町) or village(mura or son, 村). In Japan, a city is separate from districts, which contain towns and villages.

Japanese addressing system

So let’s make an example, since it’s always great fun for me to figure out the address again when I try to order the SIM card to the hotel address. A good example would be a randomly selected and nice hotel in Nakahara-ku:

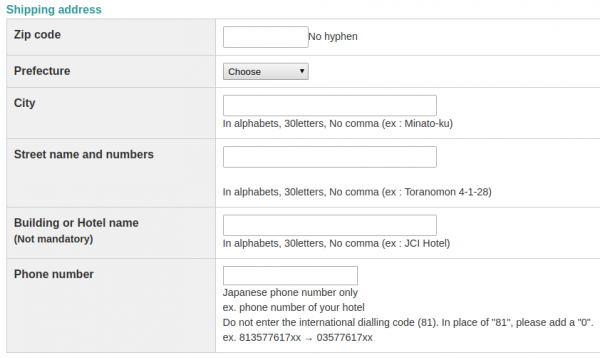

The typical english-language online order form / address entry form for shipping SIM cards to hotels gives you this interface:

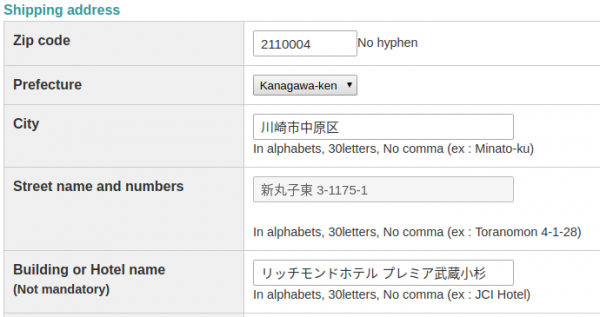

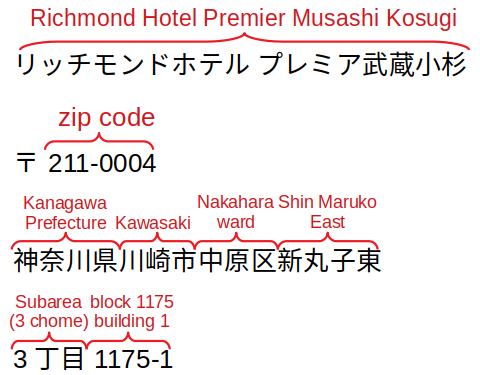

Ha! Now that’s a challenge, right? At first glance its not obvious but if you take a look at the structure of the address it opens up:

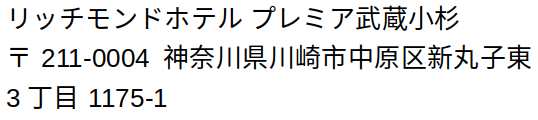

And so, this will reach it’s destination: